Incredibly, Australia has no mandatory fuel efficiency standard for light vehicles.

As has widely been reported, the Australian Government is currently consulting on a fuel efficiency standard (FES) to improve the fuel efficiency of vehicles imported in Australia.

However, such standards are not entirely straightforward and hopefully this article will help demystify some of the details. When the advocacy from various groups inevitably spills out into the public discourse, it will help to have a basic understanding of the terms and various aspects of an FES.

Despite its name, the FES is not so much a fuel efficiency standard as a tailpipe emissions standard. The limits in these standards are typically set in grams of CO2-equivalent per kilometre. From here on, we’ll just call it an emissions standard and then we can do away with another acronym.

Starting with the basics, the idea of an emissions standard is that in any given year, an emissions target applies to the entire fleet of vehicles a supplier sells that year. A manufacturer is allowed to sell individual vehicles that exceed this target, but to reach the target for the whole fleet, higher emitting vehicles must be balanced by selling lower emissions vehicles that come under the target.

Here is a hypothetical example. Assume the target for the current year is 95 grams per kilometre. A manufacturer, called ACME Inc., goes about selling its range of vehicles throughout the year. Different models have different tailpipe emissions and are sold in different volumes.

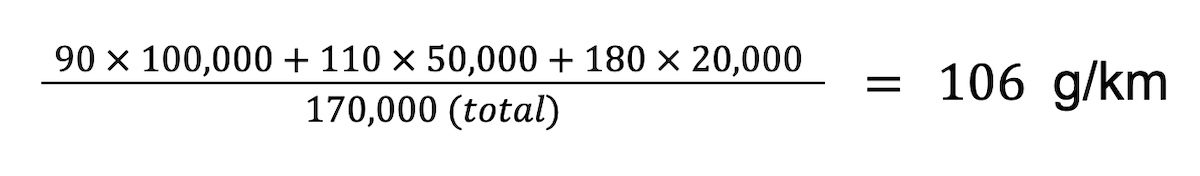

Suppose ACME has three models available: a hybrid with 90 g/km emissions, a petrol sedan with 110 g/km and a large SUV with 180 g/km. The hybrid model sold 100,000 units, the sedan sold 50,000 units and the SUV sold 20,000 units. Calculating the sales-weighted average:

The sales-weighted average is 106 g/km for ACME’s fleet. This is 11 g/km over the 95 g/km target. If a penalty was set at $100 per gram over the target, ACME would have to pay $1,100 for every vehicle they sold that year. That’s $187 million in penalties.

Electric vehicle (EV) sales really help manufacturers get their sales-weighted averages down because EV tailpipe CO2 emissions are zero.

Every EV sold allows companies like ACME to also sell a high emitting SUV and still be on track to reach the emissions target. This is precisely why manufacturers have been sending EVs to Europe. They don’t just get a sale for the EV in Europe, they also get the financial benefit of avoiding stiff penalties.

This description of an emissions standard covers the basics, but it is overly simplistic. Various tweaks have been made to this model in countries around the world and many of these design elements are up for consideration in Australia.

Emissions trajectory

An important design element is the trajectory. Since we want to cut our transport emissions, we have to tighten the emissions target down to zero over time.

EU targets are updated every five years whereas New Zealand targets tighten annually. Options for the trajectory include starting slow with deeper cuts later, a straight line trajectory, and starting fast with shallower cuts later.

There are reasonable arguments for all of these options, but the inescapable conclusion is that we have to reach zero emissions eventually, which will leave little room for even plug-in hybrids. Some manufacturers are more ready for this than others.

Limit curves

In other countries, a compromise was made that recognises that there are legitimate needs for larger, heavier vehicles and that these vehicles tend to have higher CO2 emissions.

Consequently, a “limit curve” was introduced. The two main types of limit curves are based on either the mass of a vehicle or its footprint (the area between the four wheels). The US uses vehicle footprint, whereas New Zealand and the EU use vehicle mass.

The figure below shows three different types of limit curve based on vehicle mass. With no adjustment for vehicle mass, the line would be horizontal: the emissions target is the same regardless of the vehicle. Instead, most standards use a line that slopes upwards, allowing heavier (or bigger) vehicles to have modestly higher CO2 emission targets.

However, this also means that lighter vehicles have more stringent standards. Some believe this works as a disincentive to building smaller, lighter vehicles.

The New Zealand standard addresses this by putting flat regions at the top and bottom of the limit curve (see figure). This adjustment eases the challenge for lighter vehicles and avoids an ever easier target for ever heavy vehicles.

Vehicle classes

Another design decision is whether to have one emissions standard covering all vehicles or two. Two classes are used in the EU: one for passenger vehicles and one for commercial vehicles like parcel vans. Dual-cab utes are not really a thing in Paris or Brussels!

Having one class covering all vehicles is likely to make the standard harder to meet for brands producing heavy SUVs and utes. In Australia, the manufacturers seem to prefer two classes, appealing to the perception that Australia is a special place that needs SUVs and dual-cab utes. Yet, this segment is where our vehicle emissions are the worst.

Flexibility mechanisms

Elsewhere in the world, flexible trading mechanisms have been introduced into emissions standards. These mechanisms are intended to reduce the costs of compliance by giving manufacturers some flexibility.

A common allowance is for manufacturers that come in under the target to generate credits which can be sold to manufacturers who are over their target.

By purchasing these credits, manufacturers can avoid paying penalties. For example, Tesla sells all of the credits it generates in Europe. Other flexibility mechanisms include allowing manufacturers to band together to meet their targets collectively, allowing credits to be banked for future years, and allowing deficits to be carried forward to future years.

Bonus credits

In the EU, it is possible for manufacturers to gain “bonus credits” through various means. These are broken down into three categories: super credits, off-cycle credits and refrigerant credits.

Super credits were an interesting innovation in the EU standard and have arguably now done their job. The idea is that every low emissions vehicle sold would be counted as two vehicles.

This gave manufacturers an even greater incentive to bring EVs to market in the EU. Now you can appreciate why manufacturers didn’t want to send any to Australia! The super credits multiplier was stepped down over time and has now been eliminated in the EU.

Off-cycle credits are awarded for various vehicle features that save fuel (and cut emissions) such as ventilated seats that might reduce the need for cabin air conditioning or highly efficient headlights. These are called off-cycle credits because these are not captured by a standardised test cycle in a lab.

A special refrigerant credit is available for using air conditioning refrigerant with a low global warming potential in the vehicle. These off-cycle and refrigerant credits are relatively minor and can only reduce a vehicle’s emissions by up to seven grams per kilometre in the EU.

Penalties

The last design decision for an emissions standard is penalties. How much should manufacturers be penalised for exceeding the CO2 target? In the EU, the penalty per vehicle is currently set at €95 per gram above the target.

This is likely to be one of the most contentious aspects of any Australian emissions standard because Australia is starting from so far behind.

It will be important, though, to have a penalty in line with other jurisdictions to avoid low emissions vehicles flowing preferentially to other markets. We can already see the effect of having no penalty for selling high emissions vehicles in Australia.

Hopefully this quick tour of vehicle emissions standards explains the key design features and will help in understanding what is being proposed when the details of an Australian FES start being discussed.

Ben Elliston is the interim chair of the ACT branch of the Australian Electric Vehicle Association. He was a co-author of AEVA’s submission to the Fuel Efficiency Standard consultation, which can be found at https://aeva.asn.au/files/2056/